Q&A: Clemencia Echeverri

Clemencia Echeverri’s video-based practice examines violence in her native Colombia. Her Q&A provides some insight into the artist and her work: here, she reflects on her relationship to form, the conceptual issues that shape her work, the inspiration behind Sin Cielo, and a current project that she is working on for Foundacion Espacio V in Mexico.

1) You started out as a painter and sculptor. Your training in sculpture is evident in your video installations; can you address the ways in which painting is present in your work?

My life in art has been driven by ideas, more so than by techniques. For me, painting has been an act that filters and chooses the forces of motive and reason to paint from an action with the body over a surface. Painting has established in me a tight bond with the body’s memory and its expansion, it is produced and driven by and from the body. For me, paint has involved letting the experience occur through the medium and translating to the spectator by making light appear. On the other hand, with photographic or video images what I practice is capturing light, trapping it and transmitting with it. In editing I have also had the experience of the process of selection, and of affecting the image that appears. It is a canvas of light that ultimately moves closer or further representing and akin to paint and drawing. In video I experience an action that also happens in painting and it is the attempt to make visible those forces of the senses that are almost never within reach of the eye.

2) The crux of your artistic practice explores violence in Colombia. What led to your decision to focus on this theme (in your work)?

I live in a country where everyday inequality, social imbalance, lack of respect, and the maneuvers of government are harder to endure. Without a doubt, I’m interested in attending and being present to those movements that alter us and demand of us an action, from a symbolic order to the poetic. Art surrounds the times, brings the past to the present and sensitizes it, gives it meaning, allows us to comprehend the movements, and the space we inhabit. This motion of time allows us to inquire deeply about those events marked by violence that have happened without pause. It has been an interesting challenge for me since it has required me to decipher that image that holds pain, horror, memory and the possible act of truth; to have a slow, empathetic and close look. I must say it has not been easy since the problem of violence involves circumstances of appearance, disappearance and flight, and meaning – it’s fundamentally framed in acts that happen to us and to understand them it is necessary to freeze them in time, arriving, slowing down, remain touching, excavating, understanding, investigating. These processes of inquiry and excavation have allowed me to bring the image to light to send it, throw it as you throw a rock, with force, with paint, with outrage. Or to throw an image to remove, disturb, destabilize. It happens as in painting, I attempt to excavate from that central force that which make such an intrinsic, painful, and brave human value.

3) Due to the nature of the subject matter, i.e. expressions of violence that stem from historical, cultural, or political contexts, has it ever happened that your work is misinterpreted or that viewers have missed the subtleties or complexities of what you are attempting to express within your work? If so, how do you respond to this?

If we find ourselves in this situation, we would have to say that art hasn’t happened and that would be a catastrophic moment for the artist. When we ask for the spectator’s ability to decipher those complexities or subtleties, the artist would have to demand greater opportunities for “learning sensibility” and expect opportunities offered by the state to its country so that art in all its expressions can become a part of culture, of the country’s interests, comprehension and understanding in a natural and ordinary way. This dialogue is built by understanding that the levels of difficulty must be overcome …to avoid converting art into a site of basic transmission… This circumstance allows them to shift towards comprehension and emerge into a relationship with an empathetic character.

4) While your work specifically examines violence as it relates to Colombia, do you see the themes in your work as relating to other histories, geographies, nations, or cultures?

I’ve always believed that what is our own makes, builds, and defines us. That would have to be the point of departure for my work. I believe that the artist that seeks to please and belong to the world without considering their own origin, without belonging to themselves is sacrificing and punishing their artwork from their own life and culture, especially by limiting their voice. A voice that works, labours to mention and transmit to all with force and power these human values that mobilize, a voice as a critical and political instrument that would have to alter the eye.

When I approach natural disasters, the conflicts among groups, or the undervaluing of species I attempt to do so with a language that could put us all in motion, that would rise us up, that calls for sentiment of solidarity in order to attempt to unite humans with their dreams and their losses. It’s about building a body of work that allows me to transform the lost voice of protest, the unmovable bleakness for flow and movement of all, feat and panic induced paralysis into gestures of emancipation.

The world is charged with social protest against the decisions of governments and their maneuvers. Art, with is force, activates this resistance from other places and makes this part of this amplified voice that echoes in diverse cultures and completes us as humans. These manifestations from art fill the sensible and visible space showing signs from the political expressions. In a variety of my work nature expresses itself violently: the emerging clamouring of screams are present in open mouths, the urban choir of women fills the salon in an expression of mourning, the sound returns the call that remains unanswered.

5) What led you to make Sin Cielo?

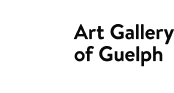

The pain of the local inhabitants and a hurting mountain. Arriving at a mining area in Colombia where nothing of what should happen there was in its place. A battered town and community tied to a mountain that has been penetrated and torn over decades. A natural space in deplorable condition.

Before that series of horrors there was nothing left to do but to rise and stand up. Art is a medium for this purpose; artwork attempts to scream and let the suffering [mountain] be heard by giving attention to that which is in crisis. To walk through the place was akin to touching a cracked skin that is about to fall to pieces; that is to say it is like facing the imminent vestiges of a place. In Marmato, Caldas, Colombia there is a small mining town that has its base in the Cauca river, the second most important river of the country. What is happening there appears to be a [death] sentence. A gold rush that is debated between a Canadian multinational and the small lot owners that work in mining informally and, in some cases, illegally. The legally accepted extraction by the multinational and the residue that is generated by small mining efforts poisons the water sources and the great Cauca River with cyanide and mercury, converging into an environmental and social tragedy of epic proportions. Art extracts a truth and a contradiction between subsistence and destruction. It allows us to not only see the events happening there, but to also create an intervention with the way in which the image is presented. To raise the voice and alert us towards regulation, control, and respect. It lets what is happening there, and what seems invisible, be seen. It takes vigilance and overflows the local, bringing a view unknown to many and reoccurring in many territories.

6) Has there been a reaction to Sin Cielo that has surprised you?

I could say that there have been reactions from viewers that have been to the place (where the work was filmed) that get a new impact from the work. This signals that art sees and lets the footprint of what is truly happening be seen through its own language, generating expanding areas of resonance. The image that emerges creates a burning friction that alters the sense with its intention and urgency that widens one’s focus and attention span. The soundtrack of the work is disquieting and many are curious about its origin. The soundtrack of Sin Cielo comes from its own tragedy as a hidden place and resists explaining the images. In that manner, it leaves them empty. The soundtrack builds another parallel image with its own rhythms and keys.

7) Can you please tell us about a current project that you are working on?

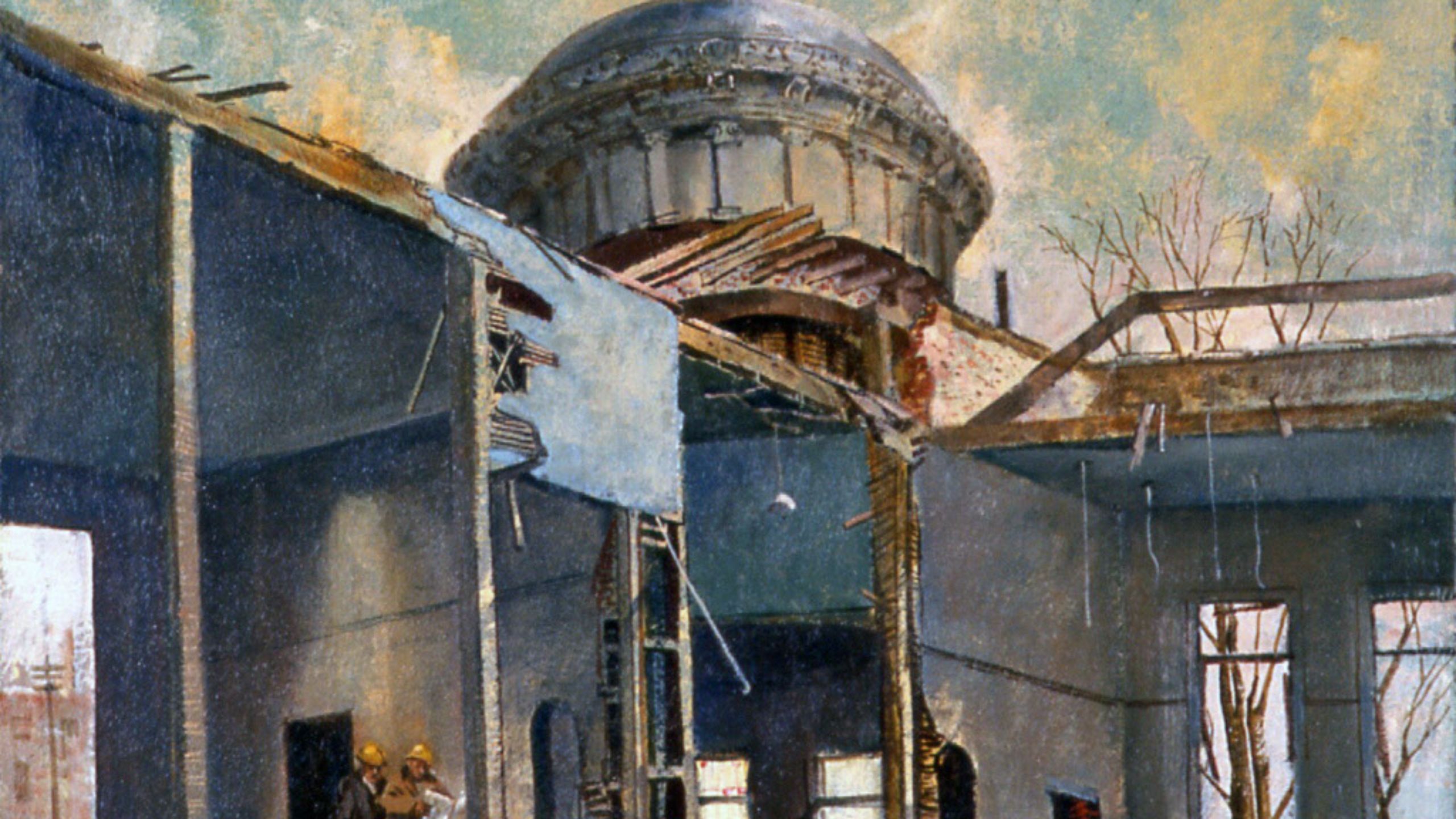

I am working on a project titled CAMPO DE BATALLO (Battlefield)which has been commissioned by the Mexican Foundation ExpacioV. The piece is a video installation about a massacre against a group of Indigenous Wayuu women from the high region of Guajira in the north of Colombia, perpetrated by paramilitaries with the purpose of claiming the territory. The work has required me to get close to the Indigenous community in that region and their mythical entrails, from the integral cosmogony among humans, the animals, the vegetables, the wind, and the mountains in an attempt to understand the effects of the massacre of this nature on this matrilineal group who have their orders and laws over their lives and the territory. With this work I propose to revive the relevance of testimony.

View More

Multimedia

January 7.2025

Multimedia

February 27.2024 February 27.2024

Multimedia

October 26.2023 October 26.2023

Multimedia

August 28.2023 September 9.2023

Multimedia

June 5.2023

Multimedia

April 5.2023

Multimedia

June 8.2022

Multimedia

February 17.2022